New York Times, December 2, 2007

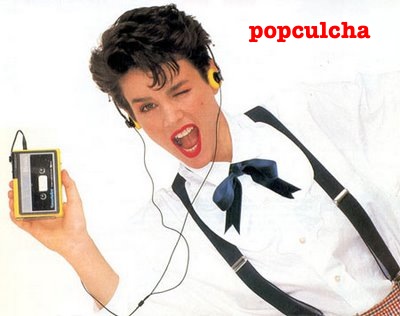

Myspacebook.past.

Friending, Ancient or Otherwise

By ALEX WRIGHT

THE growing popularity of social networking sites like Facebook, MySpace and Second Life has thrust many of us into a new world where we make “friends” with people we barely know, scrawl messages on each other’s walls and project our identities using totem-like visual symbols.

We’re making up the rules as we go. But is this world as new as it seems?

Academic researchers are starting to examine that question by taking an unusual tack: exploring the parallels between online social networks and tribal societies. In the collective patter of profile-surfing, messaging and “friending,” they see the resurgence of ancient patterns of oral communication.

“Orality is the base of all human experience,” says Lance Strate, a communications professor at Fordham University and devoted MySpace user. He says he is convinced that the popularity of social networks stems from their appeal to deep-seated, prehistoric patterns of human communication. “We evolved with speech,” he says. “We didn’t evolve with writing.”

The growth of social networks — and the Internet as a whole — stems largely from an outpouring of expression that often feels more like “talking” than writing: blog posts, comments, homemade videos and, lately, an outpouring of epigrammatic one-liners broadcast using services like Twitter and Facebook status updates (usually proving Gertrude Stein’s maxim that “literature is not remarks”).

“If you examine the Web through the lens of orality, you can’t help but see it everywhere,” says Irwin Chen, a design instructor at Parsons who is developing a new course to explore the emergence of oral culture online. “Orality is participatory, interactive, communal and focused on the present. The Web is all of these things.”

An early student of electronic orality was the Rev. Walter J. Ong, a professor at St. Louis University and student of Marshall McLuhan who coined the term “secondary orality” in 1982 to describe the tendency of electronic media to echo the cadences of earlier oral cultures. The work of Father Ong, who died in 2003, seems especially prescient in light of the social-networking phenomenon. “Oral communication,” as he put it, “unites people in groups.”

In other words, oral culture means more than just talking. There are subtler —and perhaps more important — social dynamics at work.

Michael Wesch, who teaches cultural anthropology at Kansas State University, spent two years living with a tribe in Papua New Guinea, studying how people forge social relationships in a purely oral culture. Now he applies the same ethnographic research methods to the rites and rituals of Facebook users.

“In tribal cultures, your identity is completely wrapped up in the question of how people know you,” he says. “When you look at Facebook, you can see the same pattern at work: people projecting their identities by demonstrating their relationships to each other. You define yourself in terms of who your friends are.”

In tribal societies, people routinely give each other jewelry, weapons and ritual objects to cement their social ties. On Facebook, people accomplish the same thing by trading symbolic sock monkeys, disco balls and hula girls.

“It’s reminiscent of how people exchange gifts in tribal cultures,” says Dr. Strate, whose MySpace page lists his 1,335 “friends” along with his academic credentials and his predilection for “Battlestar Galactica.”

As intriguing as these parallels may be, they only stretch so far. There are big differences between real oral cultures and the virtual kind. In tribal societies, forging social bonds is a matter of survival; on the Internet, far less so. There is presumably no tribal antecedent for popular Facebook rituals like “poking,” virtual sheep-tossing or drunk-dialing your friends.

Then there’s the question of who really counts as a “friend.” In tribal societies, people develop bonds through direct, ongoing face-to-face contact. The Web eliminates that need for physical proximity, enabling people to declare friendships on the basis of otherwise flimsy connections.

“With social networks, there’s a fascination with intimacy because it simulates face-to-face communication,” Dr. Wesch says. “But there’s also this fundamental distance. That distance makes it safe for people to connect through weak ties where they can have the appearance of a connection because it’s safe.”

And while tribal cultures typically engage in highly formalized rituals, social networks seem to encourage a level of casualness and familiarity that would be unthinkable in traditional oral cultures. “Secondary orality has a leveling effect,” Dr. Strate says. “In a primary oral culture, you would probably refer to me as ‘Dr. Strate,’ but on MySpace, everyone calls me ‘Lance.’ ”

As more of us shepherd our social relationships online, will this leveling effect begin to shape the way we relate to each other in the offline world as well? Dr. Wesch, for one, says he worries that the rise of secondary orality may have a paradoxical consequence: “It may be gobbling up what’s left of our real oral culture.”

The more time we spend “talking” online, the less time we spend, well, talking. And as we stretch the definition of a friend to encompass people we may never actually meet, will the strength of our real-world friendships grow diluted as we immerse ourselves in a lattice of hyperlinked “friends”?

Still, the sheer popularity of social networking seems to suggest that for many, these environments strike a deep, perhaps even primal chord. “They fulfill our need to be recognized as human beings, and as members of a community,” Dr. Strate says. “We all want to be told: You exist.”