Great article by David Owen, in the New Yorker, on Muzak.

[Dana McKelvey says] "When we make a program, we pay a lot of attention to the way songs segue. It’s not like songs on the radio, or songs on a CD. Take Armani Exchange. Shoppers there are looking for clothes that are hip and chic and cool. They’re twenty-five to thirty-five years old, and they want something to wear to a party or a club, and as they shop they want to feel like they’re already there. So you make the store sound like the coolest bar in town. You think about that when you pick the songs, and you pay special attention to the sequencing, and then you cross-fade and beat-match and never break the momentum, because you want the program to sound like a d.j.’s mix"...

McKelvey, a creative manager at Muzak, is one of twenty-two “audio architects”—the company’s term for its program designers. All but two are in their twenties or thirties, and all have serious, eclectic, long-term relationships with music...

People at Muzak sometimes speak of a song’s “topology,” the cultural and temporal associations that it carries with it, like a hidden refrain. When McKelvey works on a program for a client whose customers represent a range of ages—such as Old Navy, whose market extends from infants to adults—she has to accommodate more than one sensibility without offending any. The task is simplified somewhat by the fact that musical eras and genres are not always moored firmly in time. Elvis Presley (who is represented in the Well by fourteen hundred and five tracks) sounds dated to many people today, but teen-agers can listen to Beatles songs from just a few years later without necessarily thinking of them as oldies...

Today, the company estimates that its daily audience is roughly a hundred million people, in more than a dozen countries, and that it supplies sixty per cent of the commercial background music in the United States...

In 1997, the company adopted [Alvin] Collis’s concept—the main element of which he called audio architecture—essentially in its entirety. Muzak went through an exhilarating period of self-examination and redefinition, and moved its headquarters from Seattle to Fort Mill—mainly for economic reasons, but also to sever itself from its stodgy past. In a relatively short time, it transformed itself from a company that sold boring background music into one that was engaged in a far more interesting activity, which it called audio branding...

A business’s background music is like an aural pheromone. It attracts some customers and repels others, and it gives pedestrians walking past the front door an immediate clue about whether they belong inside. A chain like J. C. Penney, whose huge customer base includes all ages and income levels, needs a program that will make everyone feel welcome, so its soundtrack contains familiar and relatively unassertive popular songs like “Kind and Generous,” by Natalie Merchant. The Hard Rock Hotel in Orlando, which appeals to a more narrowly focussed audience, plays “Girls, Girls, Girls,” by Mötley Crüe, and cranks up the volume. (Imagine how teen-agers would perceive the jeans and t-shirts at Abercrombie & Fitch—not a Muzak client—if those stores played country-and-Western hits.) Audio architects have to keep all this in mind as they build their programs. They also have to be aware of certain broad truths about background music: bass solos are difficult to hear, extended electric-guitar solos annoy male sports-bar customers, drum solos annoy almost everyone, and Bob Dylan’s harmonica can make it hard for office workers to concentrate. Audio architects also have to screen lyrics carefully. They removed the INXS hit “Devil Inside” from many of the company’s playlists after a devout Christian complained, and they are ever vigilant for the word “funk,” which almost everyone mistakes for something else...

Dave Keller, who is the creative director of the company’s music department, told me recently, “Audio architecture involves looking at a client’s brand, and then matching music to the attributes of that brand. In its simplest form, you use keywords to define a personality for the brand. You might say that it’s bright, or energetic, or fun, or classic, or something like that. And then you find music with a subtext that reinforces that personality. This all really comes from Alvin Collis’s vision”...

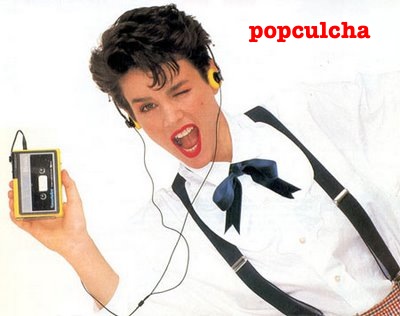

During Muzak’s early decades, office workers and others sometimes complained that public background music was an invasion of privacy. Some people feel that way today, although the first thing many of us do when we find ourselves alone with our thoughts is to reach for the handiest means of drowning them out—by putting on a pair of headphones, say, or by sliding a disk into the car’s CD player. Audio architecture is a compelling concept because the human response to musical accompaniment is powerful and involuntary. “Our biggest competitor,” a member of Muzak’s marketing department told me, “is silence.”

Footnote: Muzak files for bankruptcy, Feb. 2009.